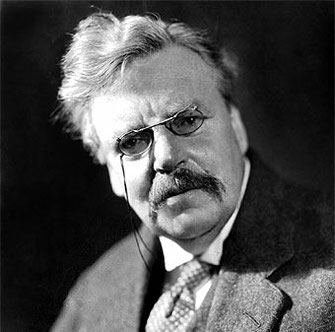

The man who was Chesterton

Although it passed quite unnoticed, the 14th of June was the 70th anniversary of the death of the good-natured and happy-spirited writer Gilbert Keith Chesterton, or GKC, as he was known to his friends as well as to his enemies.

He was a great man from many points of view, beginning with his large physical size. It made him the politest man in England, allowing him to stand up and offer his seat on a tram to two ladies at a time. He was also a great novelist, essayist, polemicist and tireless writer. He wrote over a hundred books and thousands of articles. British publishers that have set out to publish his complete works are still digging up and uncovering the vast majority of his writing a century after his demise.

Chesterton brings to mind many things including his relentless pursuit of truth and the important influence he had and continues to have on converting others, famous and not, to Christianity (for example, C. S. Lewis). There was also his tireless struggle for justice and goodness, his influence on culture, religion and politics in the UK and his literary talent. What is undoubtedly little known, but especially prized by this writer, is his disregard for so-called free verse. He considered this revolution in poetics the equivalent of "sleeping in a ditch" and calling it a "new school of architecture". Background music, which was becoming more and more ubiquitous in his day, made him uncomfortable and upset. As he explained, you go to a restaurant to share a meal and chat with friends, not to listen to music. Just the same, you don't go to a concert and take a packed lunch.

Certainly, these things have all been better discussed elsewhere and in more competent settings than this one. But, perhaps it is appropriate to mention here his love for Spain, which is not always well understood and valued in the UK where he was born.

Touching on a delicate point, for example, he fought against the deeply ingrained belief in England that Philip II was the precise embodiment of grim religious intransigence. For generations, the British have held an image of Spain as an intolerant and despotic nation under a tyrannical monarch which the English, as a peace-loving country, had no choice but to confront. This idea of England as the last bastion of liberty in tyrannical times has been emblazoned on the minds of the British by figures such as the aforementioned Philip II, Napoleon, William II and Hitler. At the same time, the British tend to exalt their own dictatorial figures like Henry VIII or vandals like Oliver Cromwell. Chesterton, on the other hand, repeatedly warned his countrymen not to forget that the religious enemies of Philip II were mostly Calvinists and men who, in their own principles and actions, were even more grim than Philip.

Taking Philip’s combined monastery and palace of San Lorenzo de El Escorial as a symbol of imperial Spain, Chesterton remarked that for a long time it represented Philip II just as Philip II had represented Spain. He went on to note that everything grim and gloomy in Philip's palace has become associated with an entire country, which is, in fact, neither grim nor gloomy. Rather, it is in many respects extremely friendly and generous. He concluded by observing that Spain is the birthplace of the picaresque novel and the comedy of errors. It isn't sad like El Escorial, but rather cheerful like Tom Jones.

Turning from essay to verse, he also wrote a wonderful poem entitled Lepanto in praise of Spain's dedication in resisting the threat of Islam while other European countries, such as France and his own homeland England, even went so far as to support Turkey. You need only remember these stanzas that would have earned Chesterton the anathema of the Church of Political Correctness, as the best tribute we Spaniards can offer to his memory:

"White founts falling in the courts of the sun,

And the Soldan of Byzantium is smiling as they run;

There is laughter like the fountains in that face of all men feared,

It stirs the forest darkness, the darkness of his beard,

It curls the blood-red crescent, the crescent of his lips,

For the inmost sea of all the earth is shaken with his ships.

They have dared the white republics up the capes of Italy,

They have dashed the Adriatic round the Lion of the Sea,

And the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss,

And called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross,

The cold queen of England is looking in the glass;

The shadow of the Valois is yawning at the Mass;

From evening isles fantastical rings faint the Spanish gun,

And the Lord upon the Golden Horn is laughing in the sun.

...

Don John laughing in the brave beard curled,

Spurning of his stirrups like the thrones of all the world,

Holding his head up for a flag of all the free.

Love-light of Spain—hurrah!

Death-light of Africa!

Don John of Austria

Is riding to the sea.

...

Don John pounding from the slaughter-painted poop,

Purpling all the ocean like a bloody pirate’s sloop,

Scarlet running over on the silvers and the golds,

Breaking of the hatches up and bursting of the holds,

Thronging of the thousands up that labour under sea

White for bliss and blind for sun and stunned for liberty.

Vivat Hispania!

Domino Gloria!

Don John of Austria

Has set his people free!

...

Cervantes on his galley sets the sword back in the sheath

(Don John of Austria rides homeward with a wreath)

And he sees across a weary land a straggling road in Spain,

Up which a lean and foolish knight forever rides in vain,

And he smiles, not as Sultans smile, and settles back the blade....

(But Don John of Austria rides home from the Crusade)”.

DENAES web page, June 2011